All that we see or seem is but a dream.

–Edgar Allen Poe

I’ve been thinking about time, realism, and surrealism.

When an author writes in first person or in third person limited, the reader is inside the head of the point-of-view character. Being inside that character’s head means they’re also in the moment, in that character’s here-and-now . The readers’ imaginations are right there, experiencing the fictional world. As readers, we feel the chill of winter wind, the adrenalin rush that sends prickles down our spine, and the warmth of a lover’s embrace. It’s all happening in the moment, in the now, and in our heads.

We’re experiencing the “now” of the story. Our own, personal now, becomes enmeshed with the now of the story. In a true sense, we inhabit the story. At least, if the author is good enoiugh.

We experience our lives—and fiction—as a sequence of nows. That’s why flashbacks are a challenge in fiction, because they disrupt this natural and intuitive flow of here-and-nows. They run the risk of breaking the reader’s always tenous connection with the story.

Writers portray fictional characters in the here-and-now as they experience it. The best fiction cyrstalizes that here-and-now and brings it to life in the readers’ imaginations. This is true even if what the character experiences is surreal.

Consider, for one example, The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland. The story stays with Alice throughout. We know what she sees, smells, hears and otherwise senses. We know what she thinks and feels. We experience her here-and-now in Wonderland by being inside her head. So, Wonderland is an example of realism, right? But Wonderland, as the Cheshire Cat might purr, is a surreal place.

Kafka’s Metamorphosis is another example. He puts us in Grogor Samsa’s head and we experience his reality as he wakes one morning, transformed into a cockroach. What happens is surreal, but Kafka relentlessly portrays the protagonisit’s here-and-now. The style is realism, used to protray a sureal here-and-now.

There are countless other examples of fiction where the author stays in a character’s here-and-now, even though that here-and-now is surreal. Sometimes, it turns out the here-and-now is a dream. Sometimes other devices come into play, and the here-and-now isn’t even sequential in the normal way.

Time travel novels move the characters to the past or future, but they most often still use the point-of-view character as an anchor. In time travel novels, the point-of-view of the character provides a coherent sequence of here-and-nows. In “By His Bootstraps,” for example, Heinlein has a scene where the point-of-view character meets and argues with two future versions of himself. Subsequently, as he ages, he experiences the same scene as each of the later versions. As readers, we experience each scene with new eyes and ears, or at least older eyes and ears. I’d say this is Rashomon-like, except that Heinlein’s story predates the Kurosawa movie by ten years.

The same kind of thing happens in The Time Traveler’s Wife, or in David Gerrold’s marvelous The Man Who Folded Himself, or even in my own novel, Timekeepers.

Dreams are another kind of reality. They’re in our head, too, so they’re just as real as anything else. Surrealist fiction often uses dreams. Consider one of the most famous examples, The Wizard Of Oz, in which everything, including all the surreal elements of Oz, turn out to be a dream. For another exmaple in The Lathe of Heaven, the protagonist’s dreams become reality.

For an example of surrealism in the visual arts, consider Dali’s painting The Persistence of Memory which shows a surreal Jungian  vision of realty. Time loses meaning with the melting clocks. The monstrous creature draped across the center evokes nightmares. Ants devouring everything, symbolize decay. The painting depicts this vision of time and memory as fluid objects, imposed on the real world, i.e., the Catalan coast in the background.

vision of realty. Time loses meaning with the melting clocks. The monstrous creature draped across the center evokes nightmares. Ants devouring everything, symbolize decay. The painting depicts this vision of time and memory as fluid objects, imposed on the real world, i.e., the Catalan coast in the background.

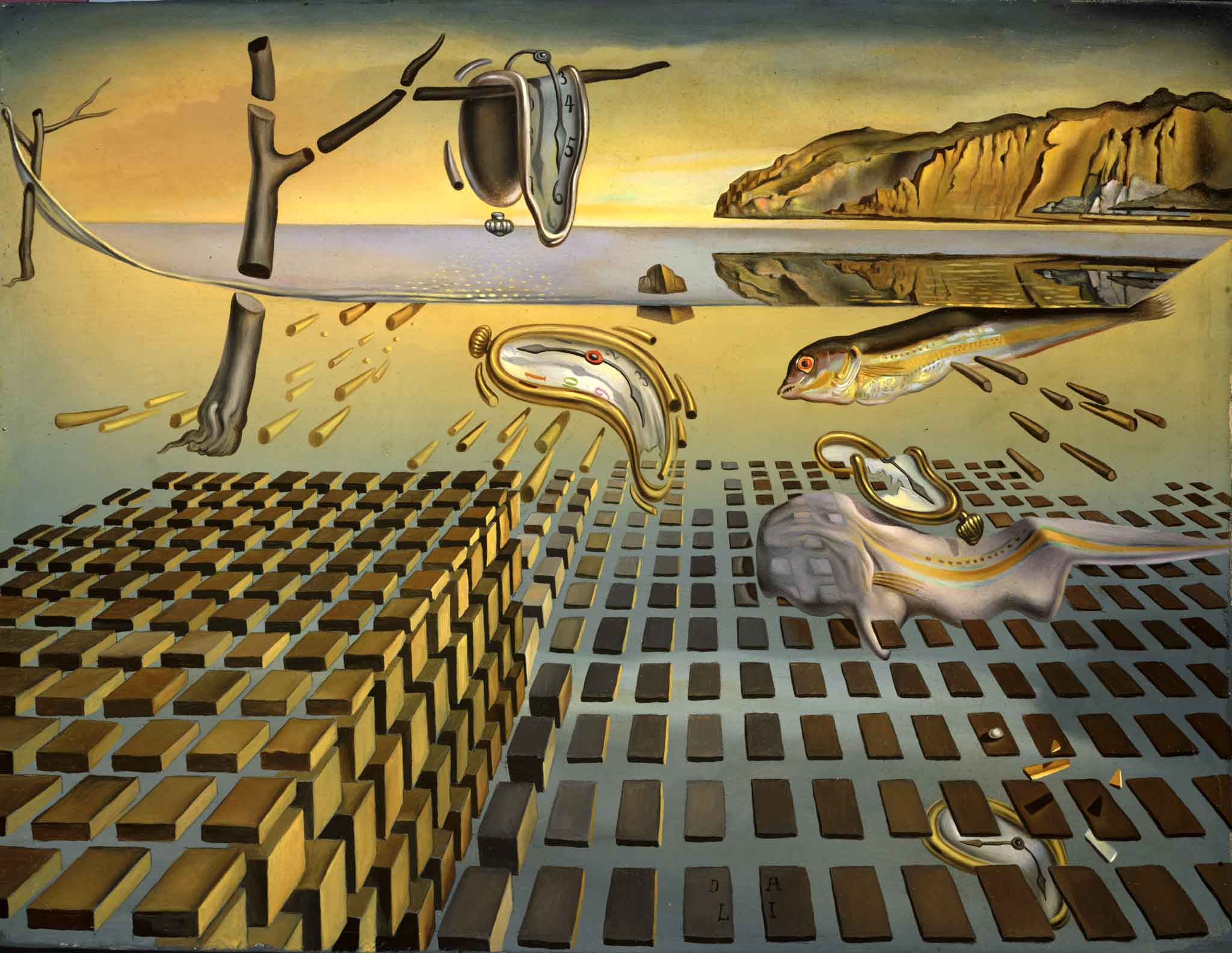

Even more interesting, though, is a later Dali painting, The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory, in which everything is disconneteced. The bottom is broken down into parts that flatten to nothingness. The Catalan coast becomes an unraveling page in the background. It’s as though atoms and quantum mechanics have replaced Jung in Dali’s portrayal of time and memory.

Even more interesting, though, is a later Dali painting, The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory, in which everything is disconneteced. The bottom is broken down into parts that flatten to nothingness. The Catalan coast becomes an unraveling page in the background. It’s as though atoms and quantum mechanics have replaced Jung in Dali’s portrayal of time and memory.

There’s a marvelous story by John Varley, “The Persistence of Vision,” that shows how vision and sound can distort our constnructed reality of the here-and-now. I’ve sometimes wondered if Dali’s paintings inspired this story. In any case, it’s worth reading.

Examples of surrealism abound in movies. One of my all-time favorite movies is David Lynch’s Mullholland Drive. Certainly, the Hollywood of that movie has many surreal elements–that’s true of the real Hollywood, as well. What’s less obvious is that the two major parts of the movie are out of order. The break occurs when Rebeka del Rio sings “Lloando,” a Spanish rendittion of the Roy Orbison classic “Crying.” Almost the entire first half of the movie shows Diane, played brilliantly by Naomi Watts, arriving and flourishing in LA. But there’s a quick flash in the opening moments, almost too fast to take in, that first shows a wizened Diane in a bleak apartment. What we’re seeing from that point forward until the “Lloroando” scene is a dream, how Diane wishes her time in LA might have gone. After Crying, we see the way her time in LA really went, all the way to the end with the wizened Diane again in her bleak apartment, all her fantasies dashed. Lynch directs the two segments with the camera’s unflinching, realistic eye, so the audience has only the barest clue of what’s really going on. A brilliant piece of realistic surreal cinema by one of America’s most talented auteurs.

But I digress.

We all live in many ‘nows.’ Some are in the past, some are in the still-to-be-experienced future, some are in the neverland of might-have-been. But wherever and whenever they are, they all are both real and the stuff of dreams. They arise in the fragile moment of a human breath, yet they are everlasting, from Big Bang to the heat-death of the multiverse and beyond.

All those nows, eternal and yet fleeting, are in our heads. All of them. Past, present, future, might-have-been, never-to-be, and fictional. All that we can know, see, or seem is right there, in our heads. And in our hearts, to be sure, but certainly in our minds and souls. That’s all and everything we can know, but surely it’s enough.

Be First to Comment